PANEL DE DISCUSION |

Renal artery embolism a reversible-misdiagnosed cause of renal ischemic disease

PROTOCOL ON EARLY DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT OF RENAL ARTERY EMBOLISM

Joan Fort Ros MD

Nephrology Department. Hospital Vall d'hebron. Barcelona, Spain

email: j_fort@hg.vhebron.es

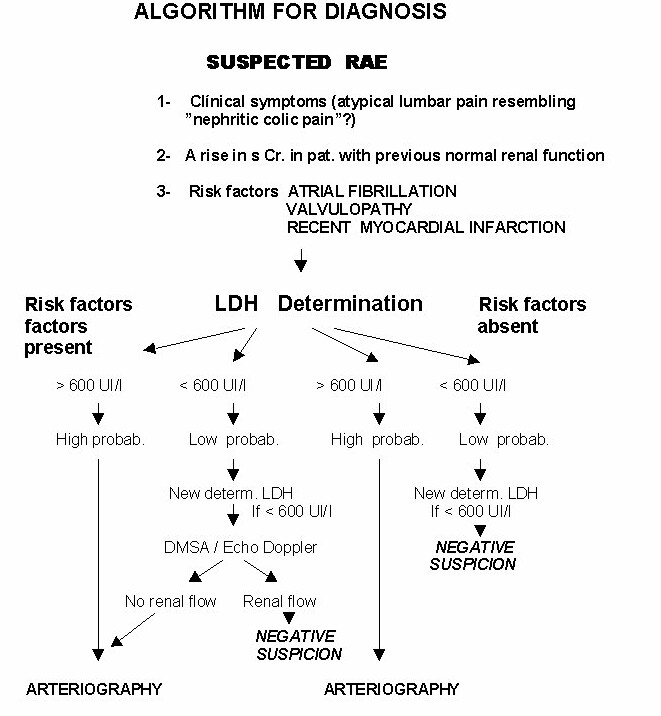

Our group (7) has recently designed an algorithm for diagnosis of renal embolism, based on LDH determination at the hospital emergency room in all patients in whom renal artery embolism is suspected (Table I)

Microscopic or chemical hematuria is the most common finding on urinalysis. Serum creatinine can be abnormal in cases of bilateral embolism or unilateral embolism in the one functional kidney.

Although transfemoral arteriography performed early on seems to offer the best diagnostic sensitivity (8) , renal power doppler, scintigraphy and computed tomography (9), have been found useful.

According to different authors (10), the duration of ischemia is an important factor for recovering renal function, however, successful late revascularization has also been reported (11). Preserved vascularization either by incomplete obstruction or by collateral circulation, enables the ischemic kidney to restore its renal output when renal artery flow is re-established and tubular lesions have healed.

Prompt treatment is enhanced by all authors. Partial or segmental renal artery occlusion and the finding of good collateral circulation is associated with favourable outcome for both surgical and fibrinolytic therapy (12). The choice of treatment is still controversial (13). Several authors (13) are in favour of surgical embolectomy when renal artery embolism is bilateral or unilateral with a solitary functioning kidney, being the embolus at the main renal artery.

Other authors (14,15), suggest that surgical embolectomy should be reserved for patients with total parenchymal embolization whose condition have failed to respond to less invasive models of therapy.

Since fibrinolityc therapy was successfully introduced by Halpern and cols (16) a lot of reports have been published using intra-arterial fibrinolysis as a therapy of choice, specially when the embolism takes place at intra-renal arteries. Both intra-arterial perfusion of Streptokinase (17) and Urokinase (18), and later on t-PA (19) have been successfully used. Success in the management of renal artery embolism lies in an early diagnosis as well as in prompt suitable treatment, bearing in mind that although the duration of renal ischemia is important, it does not correlate directly with renal damage, especially if incomplete obstruction or collateral circulation is present.

Acute renal failure due to RAE should be considered in the differential diagnosis of elderly patients with atrial fibrillation or valvular cardiopathy suffering from abnormal lumbar pain and anuria, which resembles nephritic cholic pain. A significant rise in serum levels of Lactate-dehydrogenase enzymes reinforces the suspicion of the diagnosis and is a good biological marker of screening.

It is well known that an appreciable number of elderly patients have only a single kidney, which contributes to glomerular filtration, the contralateral kidney being non-functional. This means that if RAE occurs, a quick diagnosis and treatment is compulsory in order to restore renal function and avoid end-stage renal disease and chronic dialysis, which in these patients is badly tolerated and entails a high social cost as well as morbidity

In all patients admitted to hospital suffering from "atypical lumbar pain" resembling nephritic colic pain or showing symptoms suggestive of RAE, especially when one of the following risk factors is present and serum levels of LDH are above 600 UI/. In those patients with on of the known risk factors and LDH serum levels < 600 UI/L, a new determination of LDH carried out six hours later should be considered. Electrocardiogram

Renal power Doppler

Renal scintigrapy

Renal computed tomogarphy

Transfemoral arteriography

Trans-esophageal echo cardiograph (in order to evaluate the presence of cardiac thrombi, responsible of embolism)

We considered SURGERY whenever embolus takes place at the main renal artery in bilateral or unilateral embolism with a solitary functional kidney.

An arteriotomy of the renal artery is carried out, followed by embolus extraction and evaluation of blood back flow. Finally an intra-arterial flushing with a solution of serum saline containing 100.000 units of Urokinase is given. Whenever possible the surgeon should avoid clamping of aorta.

When embolus occurs in the branches of the renal arteries within the kidney, FIBRINOLYTIC THERAPY is recommended.

Urokinase is currently given immediately after arteriography, via a catheter in the main renal artery at an initial dose of 4000 IU/min for 2-4 hours an then at a reduced dose of 1000-2000 IU/min for 8 hours or longer. Radiological control is used to monitor the embolus. If it persists, urokinase perfusion is prolonged; if revascularization is achieved, the catheter is removed and sodium heparin perfusion is administered for 24 hours to keep the activated partial thromboplastin time ratio at 1.5-2.

A long time lapse after embolism occurs should not be considered a contraindication for revascularization when arteriography shows signs of viability

In those patients in whom either surgery or fibrinolytics are contraindicated, treatment with heparin should be considered in order to avoid further embolic episodes. In those who are actively bleeding or with critical clinical status only conservative measures are indicated.

.

Before starting fibrinolytics

§ Thrombin time

§ Partial Thromboplastin time (PTT)

§ Prothrombin time

§ Platelet counts

§ Thrombin time (it should be kept between 2-5 times the normal control value)

§ Fibrin Degradation Products (FDP)

§ Fibrinogen (should be always > 0,5 gr)

The exclusion criteria for fibrinolytic therapy were described in 1980 in the "Consensus Development Conference"

a) Absolute contraindication: active haemorrhage, recent cerebrovascular accident, and active intracranial process.

b) Major relative contraindication: major surgery, peripartum, puncture biopsy of an organ, recent gastrointestinal haemorrhage, severe arterial hypertension

c) Minor relative contraindication: recent cardiopulmonary resuscitation manoeuvres, presence of heart thrombi, bacterial endocarditis, age over 75 years, haemorrhage retinopathy

The presence of intracardiac thrombi should be evaluated by ultrasound. Although this factor is only a relative contraindication, the possibility that microemboli can be produced from the major thrombus during fibrinolytic treatment must be considered in the choice of therapy.

We have to bear in mind that only when bilateral occlusion of the renal arteries or when a solitary functional kidney is affected is surgery compulsory to salvage renal function. On the other hand if embolism occurs in one of the two functioning kidneys in a high-risk patient, it may be safer to accept the loss of the kidney and avoid aggressive therapy. Although fibrinolytics are a less invasive option than surgery in the severely ill patients with cardiovascular compromise, its use still carries a certain risk.

1- Gleen JF, Boyce WH, Kaufman JJ. Cirugía urológica. Barcelona Ed.Salvat 1986;298-298

2- Traube L. Uber den Zusammenhang vo Herz and Nierenkrankheit. Berlin. A Hirschwald 1856;77

3- Hoxie HJ, Coggin CB. Renal infarction. Statistical study of two hundred and five cases and detailed report of an unusual case. Arc. Int. Med,1940; 65:587-594.

4- Lessman RK, Johnson SF, Coburn JW et al. Renal artery embolism:clinical features and long-term follow-up of 17 cases 1978; 89:477.

5- Winzelberg GG, Hull JD, Agar JW, et al. Elevation of serum lactate-dehydrogenase levels in renal infarction. JAMA 1979;247:268.

6- Gault MH, Streiner G. Serum and urinary enzyme activity after reanl infarction. Arc. Int. Med 1972;129:958

7- Fort J, Segarra JA, Camps J, et al. Diagnostico precoz del embolismo de arteria renal mediante determinación de LDH en urgencias de un gran hospital. Nefrología 1998;vol XVIII sup 3:26.

8- Hansen KJ, Tribble RW, Reavis SW et al. Renal duplex sonography; evaluation of clinical utility. J Vasc Surg 1990;12(3):227

9- Perkins RP, Jacobsen DS, Feder FP et al. Retourn of renal function after late embolectomy. Report of a case. N Engl J Med 1967;276:1194

10- Ouriel K, Andrus CH, Ricotta et al. Acute renal artery occlussion: when is revascularization justified?. J Vasc Surg 1987;5 (2):348

11- Fort J, Camps J, Ruiz P,et al. Renal artery embolism successfully revascularized by surgery after 5 days' anuria. Is it never too late ?. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1996;11:1843

12- Blum V, Billman P, Krause T. Effect of local low-dose thrombolysis on clinical outcome in acute embolic renal artery occlussion. Radiology 1993;189:549

13- Bouttier S, Valverde JP, Lacombe M. Renal artery emboli: the role of surgical treatment. Ann Vasc Surg 1998;2:161

14- Moyer JD, Rao CN, Widrich C et al. Conservative management of renal artery embolus. J Urol 1973;109:138

15- Nicholas GG, E de Muth EWJr. Treatment of renal artery embolism. Arch Surg 1984;98:552

16- Halpern M. Acute renal artery embolus: a concept of diagnosis and treatment. J. Urol 1967;98:552

17- Pilmore HL, Walker RJ, Salomon C et al. Acute bilateral renal artery occlussion: successfull revascularization with Streptokinase. Am J Nephrol 1995;15:90

18- Fischer C, Konnak J, Chop KJ et al. Renal artery embolism: therapy with intra-arterial thrombolytic therapy. J Urol 1981;125:78:402

19- Mügge A, Gulba C, Fre U et al. Renal artery embolism: thrombolysis with recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator. J Inter Med 1990;228:279.

Renal artery embolism (RAE) is an infrequent but significant cause of renal loss in patients suffering either from valvular cardiopathy or from aortic atheromatosis. (1) The first bibliographic reference regarding kidney embolic disease dates back to 1856. (2) Since clinical diagnosis is quite difficult, the real incidence is probably underestimated, as was suggested by Hoxie et al in 1940. (3)

It is known that diagnosis of unilateral embolism can often be too late and can even go undetected. Laboratory analyses can reveal renal insufficiency only in patients suffering from bilateral renal embolism or in those with unilateral renal embolism in which the contralateral kidney is nonfunctional or has been removed. More recently, other authors (4) have reported that correct diagnosis at admission was made in only 4 out of 17 patients diagnosed with renal artery embolism.

The rise in Lactate-dehydrogenase serum levels (fractions I and II) has been considered a good biological marker of screening in patients suffering from embolism (5) despite the fact that it can occur in many other conditions. Serum LDH levels remain elevated for some time after renal artery embolism occurs (6). Slight elevations of serum glutamic-oxalacetic transaminase (SGOT), glutamic-pyruvic transaminase (SGPT) and alkaline phosphatase values have been described, but they are less reliable indicators.

RATIONALE

WHEN RENAL ARTERY EMBOLISM SHOULD BE SUSPECTED ?

Renal power Doppler ecography and renal scintigraphy would be of some help in order to check the patency of renal flow as its is shown in the algorithm of diagnosis.

ˇ Valvular cardiopathy

ˇ Atrial fibrillation

ˇ Recent acute myocardial infarction

COMPLEMENTARY PROCEDURES

TREATMENT

THERAPEUTIC MONITORING

During fibrinolytic therapy

CONTRAINDICATIONS FOR FIBRINOLYTIC THERAPY

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

BIBLIOGRAPHY