|

Paneles de Discussión

Paneais de Discussio |

"Chronic kidney disease: Management strategies"Malvinder S. Parmar MD, FRCPC, FACP(Reprinted with pith permission, BMJ)Director of Dialysis. Director, Medical Program

atbeat@ntl.sympatico.ca |

Summary points: In chronic kidney disease,

|

Diagnosis:

Chronic renal failure disease is defined as either kidney damage or glomerular filtration rate (GFR) <60 ml/min for > 3 months2. This invariably is a progressive process that results in ESRD.

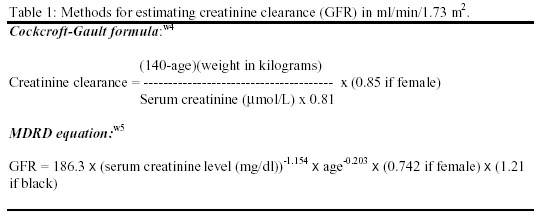

Serum creatinine is commonly used to estimate creatinine clearance but is a poor predictor of GFR, as it may be influenced in unpredictable ways by assay techniques, endogenous and exogenous substances, renal tubular handling of creatinine, and other factors (age, sex, body weight, muscle mass, diet, drugs etc)3. GFR is the "gold standard" for determining kidney function but its measurement remains cumbersome. Hence, for practical purposes, calculated creatinine clearance is used as a correlate of GFR and is commonly estimated (Table 1) using Cockcroft-Gault formulaw4 or recently described Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) equationw5. (126 words)

Stages of chronic kidney disease:

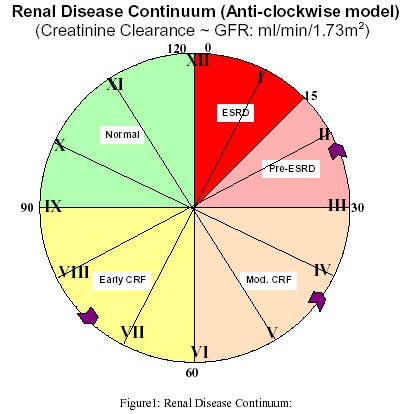

Chronic kidney disease is divided into five stages (Table 2, Figure 1) based on renal function. Pathogenesis of progression is complex and is beyond the scope of this review. However, kidney disease often progresses by "common pathway" mechanisms, irrespective of the initiating insult4. In animal models, a reduction in nephron mass exposes the remaining nephrons to adaptive hemodynamic changes that sustain renal function initially but are detrimental in the long-term5.

Early detection:

Renal disease is often progressive once GFR falls by 25% of normal. Early detection is important to prevent further injury and progressive loss of renal function.

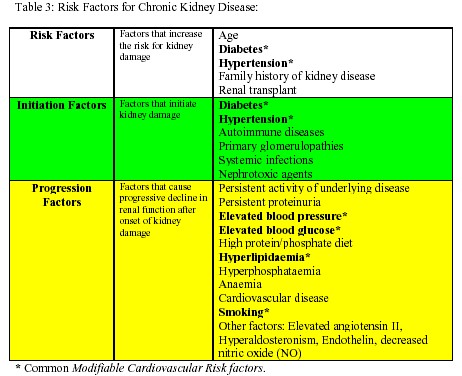

High-risk patients (table 3) should undergo evaluation for markers of kidney damage (albuminuria, abnormal urine sediment, elevated serum creatinine) and for level of renal function (estimation of GFR from serum creatinine) initially and at periodic intervals depending on the underlying disease process and stage of kidney disease. It is important to identify and effectively treat potentially reversible causes (table 4) if sudden decline in renal function is observed.

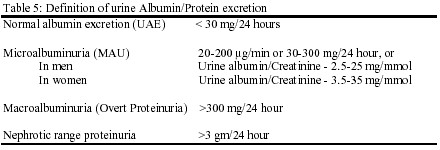

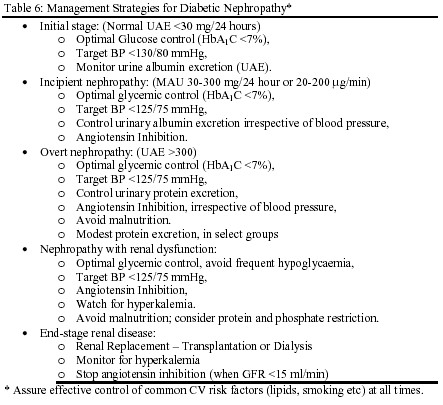

Diabetes:

Diabetes is a prevalent cause of CRF and accounts for a large part of growth ESRD in the United Statesw2. Effective glycemic and blood pressure control blunt its renal complications.

Meticulous blood glucose control has conclusively shown reduction in the development of microalbuminuria by 35% in type 1 diabetes (The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial - DCCT)6 and in type 2 diabetes (United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study - UKPDS)7. Other studies in parallel suggested that glycemic control reduce the progression of diabetic kidney disease8. Adequate blood pressure control with a variety of antihypertensive agents including angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors has shown to delay the progression of albuminuria in both type 19 and type 210 diabetes mellitus. Recently angiotensin receptor blockers have shown renoprotective effects in both early11 and late12,13 nephropathy due to type 2 diabetes.

Hypertension:

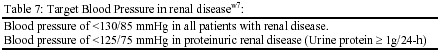

Hypertension is a well-established cause, common complication, and an important risk factor for progression of kidney disease. Controlling hypertension is the most important intervention to slow the progression therefore.w6

Any antihypertensive agents may be appropriate but ACE inhibitors are particularly effective in slowing progression of renal insufficiency in patients with and without diabetes mellitus by reducing angiotensin II effects on renal hemodynamics, local growth factors, and perhaps glomerular permselectivity15. Non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers are also shown to retard progression of renal insufficiency in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Recently, angiotensin receptor blockers (Irbesartan and Losartan) have shown renoprotective effect in diabetic nephropathy independent of blood pressure reduction11-13. Early detection and effective treatment of hypertension to target levels (Table 7) is essential. The benefit of aggressive blood pressure control is most pronounced in patients with urine protein of >3 g/24-hw6.

Reducing Proteinuria:

Proteinuria, previously considered a marker of kidney disease, is itself pathogenic and is single best predictor of disease progression. Reducing urinary protein excretion slows progressive decline in renal function in both diabetic and non-diabetic kidney disease.

Angiotensin blockade with ACE-inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers at comparable levels of blood pressure control are more effective than conventional antihypertensive agents in reducing proteinuria, GFR decline and progression to ESRD 11-14, w8-11.

Dietary Protein Intake:

The role of dietary protein restriction in chronic kidney disease remains controversialw6,15,16. The largest controlled study initially failed to find an effect of protein restriction17 but secondary analysis based on achieved protein intake suggested that low protein diet slows the progression. However, early dietary review is necessary to assure adequate energy intake, maintain optimal nutrition and avoid malnutrition. (58 words)

Dyslipidaemia:

Lipid abnormalities may be evident with only mild renal impairment and contributes to progression of chronic kidney disease and increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. A meta-analysis of 13 controlled trials showed that HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) decreased proteinuria and preserved GFR in patients with renal disease, an effect not entirely explained by reduction in blood cholesterol18 .

Phosphate and PTH control

Hyperparathyroidism is one of the earliest manifestations of impaired renal function19 and minor changes in bones have been demonstrated in patients with a GFR of 60 ml/min20. Renal tissue calcium-phosphate precipitation begins early and may influence the rate of progression of kidney disease and is closely related to hyperphosphataemia and calcium-phosphate (Ca x P) product. Calcium-phosphate precipitation should be reduced by adequate fluid intake, modest dietary phosphate restriction and administration of phosphate binders to correct serum phosphate (table 8). Dietary phosphate should be restricted before GFR falls below 40 ml/min, and before development of hyperparathyroidism. The use of vitamin D supplements during chronic kidney disease is controversial.

Smoking Cessation:

Smoking, besides increasing the risk of cardiovascular events, is an independent risk factor for development of ESRD in men with kidney disease21. Smoking cessation alone may reduce the risk of disease progression by 30 percent in type 2 diabetes22.

Anaemia:

Anaemia of chronic kidney disease begins when GFR falls below 30-35% of normal and is normochromic and normocytic. This is primarily due to decreased erythropoietin (EPO) production by the failing kidney23 but other causes might be responsible and should be considered. Whether anaemia accelerates the progression of kidney disease is controversial. However, it is independently associated with the development of left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) and other cardiovascular complications24 in a vicious cycle (Figure 2).

Treatment of anaemia with erythropoietin (rHuEPO) may slow progression of chronic kidney disease but requires further study. Treatment of anaemia results in partial regression of LVH in both pre-ESRD and dialysis patients25 and has reduced the frequency of heart failure and hospitalisation among dialysis patients26.

Both NKF-DOQI27 and European best practice28 guidelines recommend evaluation of anaemia when haemoglobin (Hb) is <11 g/dL, and consider rHuEPO if Hb is consistently <11 g/dL to keep target Hb of >11 g/dL. (78 words)

Prevention or attenuation of complications and co-morbidities:

Malnutrition:

The prevalence of hypoalbuminemia is high among patients beginning dialysis, of multi-factorial origin and associated with poor outcome. Hypoalbuminemia may be a reflection of chronic inflammation than nutrition per se. Spontaneous protein intake begins to decrease when GFR falls below 50 ml/min. Progressive decline in renal function causes decreased appetite thereby increasing risk of malnutrition. Hence, early dietary review is important to avoid malnutrition. Adequate dialysis is important to maintain optimal nutrition.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD):

The prevalence, incidence and prognosis of clinical CVD is not known with precision in renal failure but begins early and is independently associated with increased cardiovascular and all-cause mortalityw12. Both traditional and uraemia-specific risk factors (anaemia, hyperphosphataemia, hyperparathyroidism) contribute to the increased prevalence of cardiovascular disease29. Cardiac disease, including left ventricular structural and functional disorders, is an important and potentially treatable co-morbidity of early kidney disease.

No specific recommendations exist for either primary or secondary prevention of CVD in patients with CKD. Most of the current practice is derived from studies in diabetic or non-renal patients. At present, in the absence of evidence, clinical judgment suggests effective control of modifiable and uraemia-specific risk factors at an early stage of renal disease; definitive guidelines for intervention await well-designed, adequately powered prospective studies.

Preparing patient for renal replacement therapy:

Integrated care by the primary care physician, nephrologist and the renal team from early stage of disease is vital to reduce overall morbidity and mortality associated with chronic kidney disease. Practical points helpful at this stage of kidney disease are summarized below.

mol/L.

mol/L. CONCLUSION:

Chronic renal failure represents a critical period in the evolution of chronic kidney disease and is associated with complications and co-morbidities that begin early in the course of CRF. These are initially sub-clinical, but progress relentlessly and may eventually become symptomatic and irreversible. Early in the course of CRF, these conditions are amenable to interventions with relatively simple therapies that have the potential to prevent adverse outcomes. Strategies for effective management of chronic renal disease are summarized in Figure 3. By acknowledging these facts, we have an excellent opportunity to change the paradigm of CRF management and improve patient outcomes

DOS-version of a program, that I have developed (with the help of Parmar Jr) based on Figure 3, that after calculating GFR, takes the reader to the computerized figure 3 and highlights the stage the patient is in, what is the main goal at that stage, and what are the major recommendations at that stage of kidney disease. Download here

References:

|

Web-based references: w1 . Ruggenenti P, Perna A, Mosconi L, Matalone M, Pisoni R, Gaspari F, Remuzzi G, on the behalf of the "GRUPPO ITAILANO DI STUDI EPIDEMIOLOGICI IN NEFROLOGIA" (GISEN): proteinuria predicts end-stage renal failure in non-diabetic chronic nephropathies. Kidney Int 1997; 52(suppl 63):S54-S57.w2 . 2000 report, Volume 1: Dialysis and Renal Transplantation, Canadian Organ Replacement Registry. Canadian Institute for Health Information, Ottawa, Ontario, June 2000.w3 . National Institute of Health. Morbidity and mortality of dialysis [consensus statement]. Ann Intern Med 1994;12:62-70.w4 . Cockcroft D, Gault M: Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron 1976; 16:31-41.w5 . Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis KB, Greene T, Rogers N, Roth D: A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: A new prediction equation. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. Ann Intern med 1999; 130:461-470.w6 . Klahr S, Levey AS, Beck GJ, Caggiula AW, Hunsicker L, Kusek JW, Striker G: The effects of dietary protein restriction and blood pressure control on the progression of chronic renal disease. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. N Engl J Med 1994; 330:878-884.w7 . The sixth report of the Joint National Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Arch Intern Med 1997; 157:2413-46.W8. Ruggenenti P, Remuzzi G: Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy for non-diabetic progressive renal disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 1997; 6:489-495.W9. The GISEN Group. Randomised placebo-controlled trial of effect of Ramipril on decline in glomerular filtration rate and risk of terminal renal failure in proteinuric, non-diabetic nephropathy. Lancet 1997; 349:1857-1863.W10. Ruggenenti P, Perna A, Gherardi G, Gaspari F, Benini R, Remuzzi G, on behalf of GISEN. Renal function and requirement for dialysis in chronic nephropathy on long-term Ramipril: REIN follow-up trial. Lancet 1998; 352:1252-1256.W11. Ruggenenti P, Perna A, Gehrardi G, Garini G, Zoccali C, Salvadori M, Scolari F, Schena FP, Remuzzi G: Renoprotective properties of ACE-inhibition in non-diabetic nephropathies with non-nephrotic proteinuria. Lancet 1999; 354:359-364.w12 . Muntner P, He J, Hamm L, Loria C, Whelton PK: Renal insufficiency and subsequent death resulting from cardiovascular disease in United States. J Am Soc Nephrol 2002; 13:745-753.w13 . Binik YM, Devins GM, Barre PE, et al: Live and Learn: Patient education delays the need to initiate renal replacement therapy in end-stage renal disease. J Nerv Mental Dis 1993; 181:371-376.w14 . Obrador GT, Pereira B: Early referral to the nephrologist and timely initiation of renal replacement therapy: A paradigm shift in the management of patients with chronic renal failure. Am J Kidney Dis 1998; 31:398-417. |

|

Additional Educational Resources:

|

|

Patient information: |