Introduction:

The clinical presentations of severe and complicated malaria vary. The prognosis is poor when associated with cerebral malaria and acute renal failure.

Material and Methods:

Clinical profile, biochemical parameters and outcome were studied in 46 adult patients of malaria requiring hospital admission in a tertiary care hospital in between April 2002 to April 2003. The data were retrieved from the medical record system by using ICD 10 code.

Result:

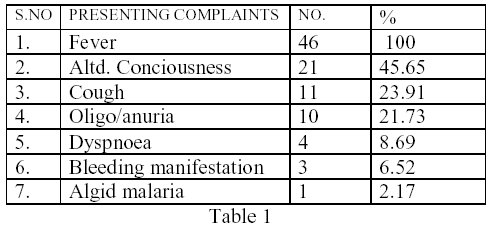

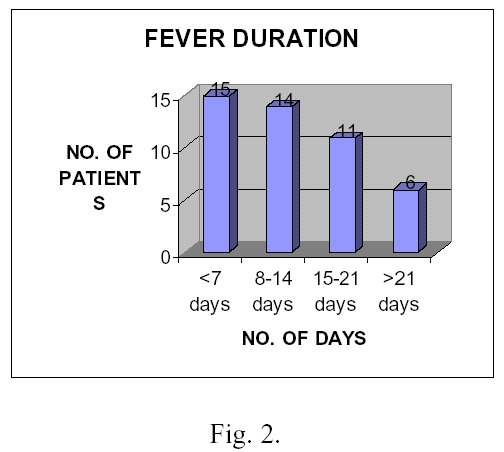

The age of the patients ranged from 15 to 60 years. Majority (n=30) of the patients were in age group of 15 to 34 years. 67% of the patients were from terai belt. Mean duration of febrile illness was 10 days at the time of presentation. 39% (n=18) patients had hepatic dysfunction and 22 %(n=10) had acute renal failure (ARF) according to WHO criteria. All patients with ARF were oligo-anuric and required dialysis support. Four patients died of which three were patients with ARF and hepatic dysfunction.

Conclusion:

Although malaria still remains a major health problem, malarial renal disease has not been reported previously from Nepal. Early initiation of anti malarial therapy, close observation for organ failure and early initiation of dialysis in ARF is instrumental in the recovery of the patient.

ACUTE RENAL FAILURE AND HEPATIC DYSFUNCITON IN MALARIA

Malaria, a protean disease is widely prevalent throughout South East Asia, Africa and Latin America. Malaria is endemic in Nepal and at present >70% of the total population of Nepal are at risk of disease1 and the disease is prevalent up to 4000 ft.

The clinical presentations and prognosis of the disease gets worse and varied when anemia, hepatosplenomegaly, and cerebral and renal involvement takes place. Renal involvement in malaria is usually caused by Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium malariae2,3,4,5,6 .Plasmodium vivax has also been incriminated in recent studies7. In general, falciparum is associated with acute renal failure (ARF) and P.malariae with Chronic Progressive Glomerulopathy8.

The hepatic involvement with malaria can be due to intravascular hemolysis, disseminated intravascular coagulation and rarely due to malaria hepatitis 9.

Objective: To study the clinical profile, biochemical parameters and outcomes in malarial patients.

Methods: The case sheets of 46 patients requiring admission in tertiary care hospital, (BPKIHS, the only tertiary care hospital in Eastern Nepal) in between April 2002 to April 2003 were retrieved from Medical Record Section under the ICD 10 and detail study of clinical features, biochemical parameters and outcomes was done. It was then analyzed using Microsoft XL 2000.

Patients having malarial parasite positive either on peripherial blood smear or buffycoat was considered as malarial patients. Acute renal failure was considered according to recently revised WHO criteria of serum creatinine >3mg/dl (265 mmol/L) with/without urine output less than 400 ml per 24 hrs despite rehydration10.

Results: In our study of 46 adult malarial patients (M=28, F=18) most of them were in age group 15-34 years (n=30). (Fig 1.)

The presenting features were those as depicted in table I. The mean duration of febrile illness was 10 days at the time of presentation. (Fig 2.)

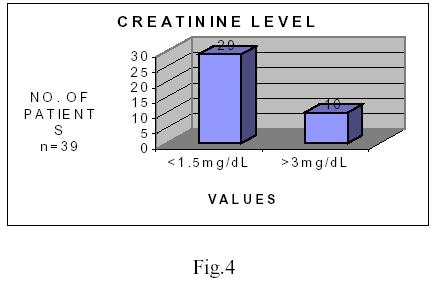

68% of the patients were anaemic (i.e. hemoglobin below 12gm/dl) and 5% of the patient had severe anemia (i.e. hemoglobin below 5gm/dl). Out of 24 patients having their bilirubin measured, 10 (i.e. 41.6%) had hepatic dysfunction (Fig 3.) i.e. total bilirubin greater than 3mg/dl. Of the total 15 patients having their liver enzymes measured, 9 had their ALT, AST and Alkaline phosphatase raised above 35 I.U./L and 120 I.U./L respectively. Out of 39 patients having their creatinine measured,10 (i.e. 25.6%) had acute renal failure (Fig.4).

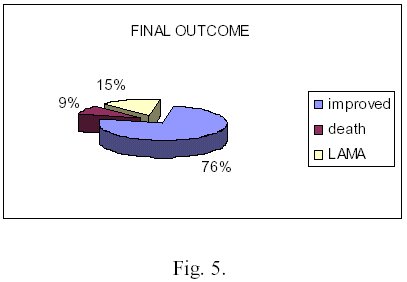

All the patients with ARF had oligo/anuria. 76% improved after antimalarial therapy and supportive measures. Most of the patients were in Quinine therapy (n=36) and remaining (n=10) were treated with artemisinin derivatives. 7 patients(i.e. 15%) died during therapy of which 3 (i.e. 43%) were having ARF (Fig. 5).

Discussion: Malaria is a major public health problem in Nepal including other countries of SouthEast Asia2, Vietnam11 and Africa12 which is endemic for the disease. Early identification of malaria and related condition and their management is extremely important to prevent morbidity and mortality related to it. The situation is more alarming with increasing incidence of falciparum malaria in the region1.

ARF is a common complication in falciparum malaria infection and occurs almost exclusively in adults and older children with an incidence of 1 to 4% 2,3,4,7,10. However, the incidence may reach up to 60% and condition is more common in males4. In our study, almost all the cases were adult and older children, mostly males and 25.6% had acute renal failure. However, 25.6%of patients having acute renal failure should be interpreted cautiously as the study place (BPKIHS) is the only tertiary care hospital in the region and the facility to diagnose and treat complicated malaria is limited to few other hospitals.

Patients with ARF are usually oliguric (<400ml/dl) or anuric (<50ml/dl)2,5,6. However, it may be normal or increased and duration of olgiuric phase usually lasts for a few days to several weeks10. In our study all patients with ARF were oligo/anuric.

Earlier studies of Thailand showed 30%of adult patients with cerebral malaria had serum creatine levels higher than 2mg/dl 7,13. Such patients had higher incidence of hypoglycemia, jaundice, more prolonged coma and pulmonary edema 7,13. Similar studies recently done in Vietnam showed that about 50% of patients had serum creatinine levels greater than 2mg/dl 7,14. What is more interesting is, 63% of the patients with ARF were jaundiced, compared with 20% of the ones without ARF11, 14. In our study, all the patients with ARF had hepatic dysfunction i.e. raised T. bilirubin level> 3 mg/dl.

Hyperbilirubinemia usually results from the complication of hemolysis and intrahepatic cholestasis rather than hepatocellular necrosis9. The true malarial hepatitis is usually distinguished by more than three fold elevation of ALT and is rare15. In our study, 41.6% had hyperbilirubinemia according to WHO criteria of severe and complicated malaria9.

ARF is a serious complication with a reported mortality of 15 to 33%16,17,18. In our case mortality was 15% (n=7) of which 3 (i.e. 43%) were having ARF.

Prognosis of the disease depends upon the severity of condition, associated extra renal complications, response to antimalarial drugs and earlier indication of dialysis. 50% to 75% of patients without dialysis rapidly die10. The selected mode of treatment is hemodialysis and should be initiated early in the course of illness, as peritoneal dialysis would be less effective because of impaired peritoneal microcirculation 2,3,6,7,11,13. However in our study all the patients had undergone peritoneal dialysis. The cause of all the patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis is due to lack of adequate no. of hemodyalysis machines and also its affordability.

Quinine is the drug of choice and is most widely used antimalarial drug in case of severe and complicated malaria10. In our study also most of the patients recovered from the quinine therapy and rest were treated with artemisinin derivatives.

From the above discussion, it shows that malarial acute renal failure and hepatic dysfunction is fairly common in Nepal. However, till date no such studies have been done and this is the first of its kind. So the true incidence and prevalence of the disease in this region needs to be reevaluated.

Thus in conclusion, malaria is an important clinical entity in these regions and the physicians should be vigilant about the deteriorating kidney function as early initiation of antimalarilal drugs and dialysis can be life saving.

REFERENCES:

1. Annual Report, Department of Health Services 2057/058 HMG Nepal, MOH: Malaria Control:pp108

2. Sitprija V. Nephrology forum. Nephropathy in falciparum malaria, kidney Int 1988;34;866

3. Barsoum Rs: Malarial acute renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrology 2000:11:2147-2154,

4. Boonpucknavig V, Sitprija V: Renal disease in acute plasmodium falciparum infection in man kidney Int 1979:16:44-52,

5. Barsoum Rs, Sitprija V: tropical Nephrology in Schier RW(ed):Diseases of the kidney and urinary tract (ed 7)Philadelphia, PA,Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2001, pp 2301-2349

6. Eiam-Oug S, Sitprija V:Falciparum malaria and the kidney : A model of inflammation , Am J kidney Dis 2000:36:1-11,

7. Eiam-Ong S: malarial nephropathy : Seminars in Nephrology, 2003 Vol 23, No 1(January),: pp21-33

8. Barsoum R: Malarial nephropathies. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1998;13: 1588-1597

9. WHO Malaria Action Program. Severe and Complicated malaria Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1986;80 (suppl) 3-50

10. WHO: severe falciparum malaria , Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2000 94:1-90, (Suppl 1)

11. Trang TT, Phu NH, Vinh H et al, acute renal failure in patients with severe falciparum malaria. Clin Infect Dis 1992;15 (5):874-80

12. Mate-kole MO, Yeboah ED, Affram Rk, et al. Blackwater fever and acute renal failure in expatriates in Africa. Renal Fail 1996; 18(3):525-531

13. Phillips RE, White NJ,Looareesuwan S, et al : Acute Renal failure in falciparum malaria in Eastern Thailand : Successful use of peritoneal dialysis. Presented at the XI international congress for tropical medicine and malaria ,Calgary , Canada, 1989,September 6-11

14. Trang TT, Phc NH, Vinh H ,et al: Acute renal failure in patients with severe falciparum malaria . Clin Infect Dis 1992,15:874-880

15. Anand Ac, Ramji C,Narula As, et al: Malarial hepatitis: A heterogeneous syndrome? Natl Med J India 1992;5(2):59-62

16. Lallo DG, Trevett AJ, Paul M et al . Severe and complicated falciparum malaria in Melanesian adults in Papua New Guinea. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1996;55(2):119124

17. Weler MW,BokerK, Horstmann RD, et al . Renal failure in a common complication in non-immune Europeans with P. falciparum malaria. Trop Med Parasitol 1991;42(2):115-118

18. Naqvi R, Ahmed E Akhtar F, et al. Predictors of outcome in malarial renal failure. Renal Fail 1996; 18(4): 685-688.

Address for correspondence:

Dr. Sanjib Kumar Sharma

Associate Professor, Internal Medicine; In-charge Dialysis Unit and Renal Disease prevention and Diabetes Clinic

Department of Internal Medicine

B P Koirala Institute of Health Sciences

Dharan. Nepal

Email: drsanjib@yahoo.com